Lifecare Kingsway Physiotherapy.

Just like Rome, the human body wasn’t built in a day and it certainly doesn’t repair itself in that time frame.

The body’s response to damage is complex and variable, it depends on the extent of damage, the type of tissue, your age, your health and many more variables you cannot control.

You cannot control how fast your body repairs itself following injury, you can only optimise it by avoiding factors that slow the normal healing process.

This includes avoiding activity that re-injures the tissue such as running after a hamstring strain or even standing on a fractured foot.

Activity that reproduces your pain and makes it more sensitive or intense is likely to limit your ability to heal, so therefore ‘no pain no gain’ is not a relevant mindset.

Just like the way your body deals with a cold or an infection, the body has a set process to deal with tissue damage.

Tissue describes a collection of similar cells which make up a type of body tissue, examples include muscle, epithelial (skin and blood vessel lining), connective (bone, ligament and tendon) and nerve.

The process is similar for each tissue, with small variations in the cells involved in the healing process.

Not every tissue will heal in the exact same manner, this is due to blood supply to the area, the function of the tissue and the ability to protect the tissue in response to injury.

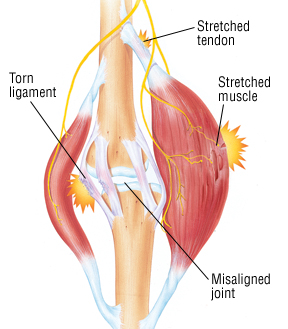

The majority of tissue injuries occur when a large amount of pressure is placed upon a structure.

The pressure, either quickly applied or accumulative over time, causes breakdown of tissue and damage occurs.

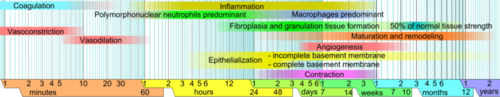

An immediate reaction begins in response to damage in the tissue, this occurs in four distinct phases.

Each phase takes time to complete and usually overlap before the next phase begins.

Phase 1: bleeding (vascular component of inflammation)

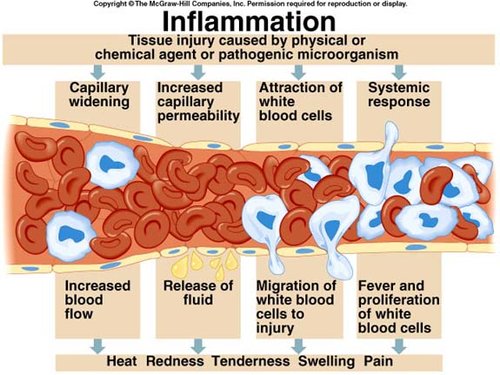

The immediate response to damaged tissue is usually bleeding and swelling around the injured tissue.

This occurs at a cellular level when cells and blood vessels that make up the damaged tissue die and release a chemical called histamine which increases the rate of fluid flooding the area from the surrounding blood vessels.

This causes dilation of blood vessels surrounding the damaged tissue, allowing migration of white blood cells, platelets and other blood products in and around the damaged tissue – starting the cellular inflammatory process.

This occurs immediately following tissue damage and is managed in minutes to hours after injury.

Phase 2: cellular inflammation phase

The arrival of blood products to the damaged site allows for the tissue to prepare for the healing process.

White blood cells, specifically leukocytes, infiltrate the damaged tissue and consume debris and dead tissue in a process called phagocytosis.

Once the damaged tissue is removed, the remaining tissue is prepared for rebuilding and the damaged cells no longer produce inflammatory chemicals, slowing down the inflammatory process.

When damaged tissue is unable to be completely cleared or removed from the damage site, inflammation continues to cycle without stopping, this is called chronic inflammation.

The normal process of inflammation spans between minutes following damage and the next 72 hours post injury.

Phase 3: proliferation

In the dying stages of inflammation, specialised cells called fibroblast begin to rapidly multiply in and around the damaged tissue in a process called proliferation.

Fibroblasts reconstruct damaged blood vessels in the area and lay down bundles of collagen to rebuild the damaged tissue at the damage site.

This may include surrounding muscle/connective/epithelial tissues that were also damaged by the abnormal load causing tissue breakdown.

Once the immature tissue is laid down, the wound begins to contract to reduce the size of the damaged site.

This begins in the first day of injury and extends up to a month post injury.

Phase 4: remodelling

Remodelling describes the maturation of immature collagen cells within the wound that are roughly laid out in the proliferation phase.

Type III collagen which is laid down in the proliferation phase is disorganised and randomly orientated.

This collagen converts during the healing process to type I, by applying gentle force such as stretch, contraction, weight bearing pressure to the healing tissue, aligning the fibres to run inline with the direction of tension and reduce the occurrence of scar tissue.

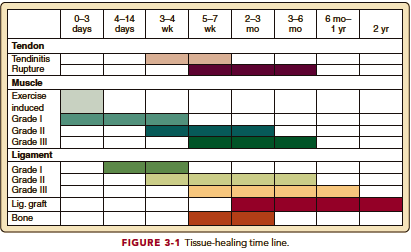

This process begins in the weeks following tissue damage and can extend over 12 months or more depending on the size and type of the wound.

This basic overview explains why tissue cannot simply heal overnight but takes weeks to months to fully restore.

As physiotherapists our job is to manage patient expectations regarding recovery from injuries and how to best manage your specific condition.

In many cases medical and surgical assistance is required based on the best possible outcome or safest approach to rehabilitation.

This will be assisted by your physiotherapist who can perform manual therapy to assist with the condition of damaged tissue and instruct on appropriate activity and exercise to facilitate tissue healing.

If you would like to consult a physiotherapist about your injury, get in touch with your local Lifecare practice.

22 DECEMBER, 2017